GOOD MANNERS, NOT ETIQUETTE

Merriam-Webster defines etiquette as “the conduct or procedure required by good breeding or prescribed by authority to be observed in social or official life.” I don’t really know what “good breeding” means, and “prescribed by authority,” sounds a little too hierarchical for my liking. Manners, “the social conduct as shown in prevalent custom,” feels more comfortable, especially when it is modified by the adjective “good.” Without the modifier, our conversations are at risk for creating frictions, strife and divisiveness, which is fraying our civil society. Witness almost any popular talk show, many blogs (especially in the comments), or conversations among politicians and other leaders. We are seeing a slow unraveling of the goodwill and mutual respect that Peter Drucker referred to as “the lubricating oil of modern organizations.”

We got a powerful reminder of this last week as participants at an event called It’s Up to Me AZ. The keynote address was delivered by Frances Hesselbein, president and CEO of the Leader to Leader Institute and editor-in-chief of Leader to Leader Journal.* She a 95-year-old leadership icon who continues to work hard, travels extensively and is consistently gracious. She spoke about the need to return to good manners, as a way of creating a climate of trust and respect.

We consider good manners a form of extending goodwill to others, even when — especially when — it is a difficult conversation.

People often see goodwill as a feeling or emotion, believing it requires that you like the person you’re talking to. Goodwill is not a feeling — it is a choice about how we bring ourselves present in any given moment. And it is a skill that can be developed. We can choose to approach a conversation with goodwill, no matter what. Even with a stranger. Even if we disagree. Even if we don’t like the other person.

As Hesselbein says, good manners are not about mindless or old-fashioned rules but rather are about “the quality and character of who we are.” Good manners are about who we choose to be in the world.

It takes manners and civility to build the “healthy, inclusive, and embracing relationships that unleash the human spirit” she said. Goodwill is foundational — it breeds a culture of accountability, commitment and collaboration. And if you’re trying to succeed in the marketplace, that kind of “good breeding” makes business sense.

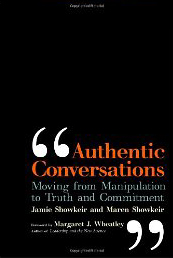

*(If you’d like a free copy of the article on Authentic Conversations we published in Leader to Leader Journal, please send us an email at info@henning-showkeir.com.)

maren

maren